Dr. Ambrose Delasco served as an Associate Instructor of Philosophy at the City College of New York from 1959 through 1968. His first book, The Primal Agenda, self-published in 1960, while difficult to find due to the fact that only 237 copies ever sold and only eight are known to exist, remains his most credible and best-selling book. In it, he expounds upon the principal of the Primal Agenda, the idea that all humans are born with an inherent destiny or will that is separate from whatever stimuli the individual might encounter in his or her life.

A regurgitation of the old nature vs. nurture debate, the Primal Agenda explains, according to Delasco, why some people from pleasant families are assholes or even murderers, and vice versa. However, two years after publication of the book, Delasco discarded this theory, calling it ‘ridiculous’ and never mentioned it again except in passing. By then he had formed perhaps his greatest and most profound theory, that of the Keystone Will.

According to Delasco’s theory of Imminent Decline, the average human specimen has a classic bell curve of psychological, intellectual, and sexual potential. There are the zero states of birth and death, and between these two brief points in time the individual passes through his or her arc of life—composed of individual attributes and the individual will affected by the will of others, illustrated in the Keystone Will Theory. Delasco also claimed that any individual’s arc of life can easily be expressed on a three-dimensional graph. His attempts to draw three-dimensional graphs on paper were largely a colossal failure because he wanted them to actually be three-dimensional, so he ended up getting rid of the Z axis completely and combining personal will and the effect of outside wills on the same axis (Y1 and Y2). The results were confusing and nonsensical.

Dr. Delasco, teaching at City College some ten years after the golden age of philosophy had passed through the halls of the school, never to return, theorized that all human sexuality was nonsense. He likened it to psychology and claimed that “any attempt to fathom the vast intricacies of the human mind and combine that wondrous potential with the bias of the individual, well . . .” Here, he stopped and took a sip of water from a mug, purple, always sitting at the corner of his desk. He loosened his tie.

“Listen,” he said, banging the cup down and causing more than a few students to flinch awake. “To try and truly understand why a person is, say, manic-depressive or homosexual, instead of corralling them into the tidy little box of the predefined term itself, is an enormous undertaking, one the common individual, much less a doctor of psychology, is willing to endure. No. In order to understand disorder, or order, or sexuality, one has to figure how the individual fits into the larger scheme of things. No one is manic-depressive, just as no one is homosexual. These are just terms created by the limited human mind to attempt to understand that which is beyond its capabilities. For the same reason we created—excuse me, Mr. Moss? Do you have something to say? So then may I continue?—For the same reason we once created gods and myths . . . with those foundations mostly destroyed, we now need to create other ways to understand our world. Like homosexuality.”

Dr. Delasco looked out over the lecture hall, its scattering of students in various stages of slump, and narrowed his eyes.

“Who in here is heterosexual?” he asked, and most students who were awake or had been listening raised their hands or shifted. “Well, so am I,” Delasco said. “And yet . . . I could have sex with, with this desk—this one right here—if I were so inclined, and if I felt a deep attraction to furniture. So would that be homosexual? Objosexual? Ridiculous. You can be a schizophrenic lesbian if you like, or a clinically depressed bisexual, but these are just terms. In the end, you are who you are due to your will and its interaction with the wills of others. Create whatever terms you want, but they’re meaningless when the enormous potential of human existence is considered. Such oversimplifications are an insult to our very humanity. Don’t look at me like that, Mr. Sheifer. What, exactly, is so funny?”

And here, the transcript of Delasco’s lecture “Common Existence and the New Hedonism” abruptly ends.

#

The Soup of Tendencies lecture consisted of Dr. Delasco attempting to demonstrate that out of any chaos of possibilities, a set of tendencies is easily definable. As often, Delasco then grafted this idea onto the human specimen by noting that out of all the possibilities for existence, some people tended to be shallow, self-centered bigots while others were kind, humble and generous. His Soup of Tendency, and by extension the idea of Universal Guilt, was an attempt to explain that this was a result of willful decisions made by an individual to define his or her existence, yet who managed, on a whole, to maintain a primal balance of tendency. Ergo, there will always good people and bad people, and there could never be an overwhelming balance of one or the other. One begets the other. So that in the sum of human possibility, whether you were a lout or a gentleman or a dunce or a genius all depended on the influences around you. To surround oneself with positivism is an effort to remain pure.

However, in a further hypothesis, Delasco stated:

“Since electrons are constantly shared by differing particles unless their valence shells are complete, such as with the noble gasses, each piece of matter consists of the matter of the objects within its vicinity. Electrons bounce from one thing to the other; now part of a water molecule in your eye, now joining with the carbon in the wooden chair on which you sit, perhaps bounding on a wave of light across the room and used temporarily by my chalk here before being scraped against the slate so you can see this mark, here, by that very same eye.”

This further explains the Soup of Tendencies because “opposites tend to attract” and “once a particle is laden with an aspect of its former self—whether from the eye of a student drunkard, the mindless carbon of a wooden chair, or the positivity of light—well, that particle, when choosing its next form, will go to the furthest opposite out of common tendency.”

His comments were met with blank stares and mouths frozen in yawn.

#

In what would be Delasco’s final lecture, he responded to a student comment that all motion was relative and therefore the universe, the galaxy, solar system and even the planet Earth were absolutely motionless, with no fixed point to determine their speed.

“Nonsense,” he was noted to have said. “Look, get your feet off that chair. Now, say you’re the Sun—no, don’t actually say it, just pretend that you’re the Sun and I’m the Earth. Right now, I’m orbiting you, correct? And if we were to fixate my speed in relation to your position, we would find me moving at about, oh, 67,000 miles per hour, correct? And now imagine that I’m the solar system and you’re at some point in the galaxy, which is this room. Not only is the Earth traveling at 67,000 miles per hour but now that is multiplied by the universal orbit of a half million miles per hour, while the galaxy itself is rotating at 1.4 million miles per hour. Since the speed of light is only 670 million miles per hour, it is safe to assume through multiplication and conjecture that we are traveling far in excess of the speed of light in relation to any fixed point in creation.”

Therefore, he concluded, with mass and time increased, “we exist like a sparrow fart in a strong wind. And due to our relative—there’s that word for you, Mr. Moss—our relative position, we have long lives and own cars and have affairs and enjoy pictures of naked women.”

Later in his lecture, Dr. Delasco tried to further quell the student’s remarks, which had turned the tide against him, by illustrating that “when walking backward, like I am now, I am still moving at incredible speeds yet somehow slower too. How, you ask? No, not just because I’m walking backward, but because I’m walking westward, with the rotation of the Earth rather than against it. Therefore, my overall speed is slightly reduced by—”

At this point, Delasco fell over a chair and injured his kidney. The lecture was over. He never returned to the lectern and died some three months later, possibly as a result of the fall.

#

According to Delasco, sweets and intercourse were the only reason to get up every day. Without the hope that perhaps this day would bring you either something sweet, or intercourse with another human, then there would be a whole flurry of suicides, or most people would just wither away into nothing and die (as they are apt to do anyway). He attempted to tie this concept to his Theory of Imminent Decline by noting that the older we get, the more we realize that we may not have intercourse that particular day, and if we do, it won’t be as satisfying as we imagined it to be. And, just as the first bite of chocolate cake is better than any other after it, so too does the lure of sweets fade away with age. We come to know what to expect of intercourse and sweets. They become routine.

At this point in the lecture, he would usually go off on a tangent about the importance of affairs, pornography, and imported candies.

#

In an off-handed mentioning of his Theory of Accumulation (it was never developed completely) Dr. Delasco suggested that as we pass through our own brief lives, we are exposed to stimuli both physical and metaphysical—memories, morals, prejudices, epistemological modes of being, the falsity of playground rules—all of which would naturally contribute to a very confused state for an individual, a psychotic state, unless something is done. Often, these aspects of existence “are incongruous or downright hostile with each other.” And this thereby causes typical individuals to “choose one over the other” and thus “solidify their beliefs and chosen memories and prejudices—everything that makes them who they are—into a calcifying mass that accumulates more and more of the same elements until the individual is a simplified humanoid, a living fossil in the psychosomatic sense. New thought, new ideas become rejected outright by the established accumulations and—”

Here, he paused dramatically but it was right before Thanksgiving break so only a handful of students were present.

“Well, this explains why bigots and judgmental assholes are so difficult to convert toward a more open mindset. It’s best to give up on these calcified individuals, and concentrate on your own accumulations, directly tied to the Soup of Tendencies theory, and accumulate the correct aspects of existence, the best particles of your opposites. It’s important that you actively and willfully build the foundations for your calcification because we will all calcify into something. But it’s up to us to determine what that something will be.”

And the lecture ended suddenly, on an unusually conclusive note, even ten minutes early.

#

Dr. Ambrose Delasco once stated in lecture, a segue concerning Nietzsche’s various physical afflictions:

“Sorrow and suffering cut deep grooves in the soul, and these are for joy to fill. Without those grooves—those pits and scars of the pain of existence—joy just slips right off a person like melting butter on a tipped skillet.”

Dr. Ambrose Delasco’s most complex concept was that of the Keystone Will. In this lecture, he utilized some four dozen balls of yarn to illustrate his concept to the class. The theory states that the individual will is truly singular and unique.

“If I decide to throw this book at Mr. Moss,” he stated to his class, waving a copy of the never-used textbook. “It will be an expression of my will that supersedes his own, which is to merely sit there with his feet up on a chair in front of him, and remain unharmed. Thus, the individual will has great power and, at the same time, a great impotence.” Delasco then sidetracked on a short discussion on impotence in males and how pornography and affairs have been shown to help. When getting back on subject, he made the class spend forty-five minutes tying themselves together with string, strand by strand.

Eventually, there were only two or three volunteers left, running lines of string from one student to the next, from the professor to each student. Most of the string was reportedly purple to “reflect the darkness of nothingness between things.” Once the class was appropriately encumbered, with thousands of feet of string connecting them all in myriad ways—one tied from her wrists to three random students, one by his neck and thigh to eight students and a chair, one secured at each limb to the light fixtures and the professor’s torso, one to three students, a doorknob and the professor’s left foot—Delasco began his important comments, standing very still so as not to disturb the strings.

“Quiet down, please. Thank you. Do you see? You’re already experiencing the effect of the Keystone Will. No, settle down. Mr. Moss, you’ve got to keep your feet up on the chair—do you see that mass of string around them? Okay. Now, this is but a humble representation of our present existence. We are all individuals, with individual wills, and yet with each enactment of our will we make noticeable reverberations in the universe, in the wills of others. As an example—”

And here, Delasco yanked his right arm—which had innumerable students tied to it in varying degrees—upward and with great force. Some students yelled out in pain and shifted, causing others to shift, and the movement rippled around the room in a strange pattern.

“Now,” he began again. “Notice how some of you were jerked painfully by the expression of my will which in turn caused others to be so affected. Yet, as far as you know, the movement might have been entirely your own, not caused by me or anybody else. Normally you can’t see or feel the strings, so often what you think is your own will is really the reaction of interacting with another’s. Notice too how several of you were not affected in the least though you could clearly perceive the expression of my will as an observer. Now, let’s try something different.”

Delasco encouraged a student to attempt to change his seat. The student gingerly maneuvered about with the taut strings while the other students groaned and had to shift or stand or bend in half in order for the student to change seats. But he did it and Delasco beamed with pride.

“This is exactly how the individual will, in a seemingly neutral act, can affect others. The expression of your will doesn’t have to be negative to cause other people great discomfort and chaos.”

He then tried to get two students to kiss, but they were both boys and finally encouraged a beautiful black girl with a string on each limb to kiss the shy Asian exchange student with his head wrapped with five strings. Their movements were said to have been so slow and deliberate, so kind, that the strings connecting them never pulled. Other students contorted themselves impossibly to help them come together and their kiss was brief, awkward, but rather beautiful. A hush had descended over the lecture hall.

“Mr. Moss,” Delasco said, teetering on one leg at the front of the class with arms mangled and contorted in the air around him. “Will you now please put down your legs?”

And as soon as he did so, the two metaphorical lovers were torn apart and a great groan went through the class as countless students shifted and jerked and their skin burned where the strings pulled and slid.

“This,” the professor said. “This is life. Now you’ve got to imagine the strings vertically too, not just horizontally. Imagine them connecting every single thing in the universe together. Notice that though you are not connected to her way over there, but by association, by degrees you are connected.”

The students stared at Delasco, standing there on one leg, some perhaps noticing him for the first time even though the final exam was next class.

“If you go around pushing your will around willy-nilly, you’ll cause endless strife and difficulty even if that isn’t your intention. Likewise, if you just sit there in passivity, you will still be subject to the will of others. If I wanted to go to the door right now, I would likely drag a bunch of you with me. And still, there was that kiss. Thank you Ms. Ebalu and Mr. Chen. Notice how when several of us work together, we make it easier, make things happen. That is the Keystone Will Theory. When the individual will can convince or motivate others toward a goal—no matter if it’s a common goal or not—then something beautiful happens. We help each other, and one day, one day,” he paused for dramatic effect, his audience in actual captivity. “One day instead of all of us pulling and yanking in our own selfish little enactments of will, one day we might realize that working together can solve every problem known to man, when the cumulative or Universal Will eclipses any individual will that would do harm or is negative or just downright mean. And we all have the Keystone Will within us.”

He stared at the class a moment longer and smiled, his thigh quivering in the air.

“Class dismissed,” he said.

And it took the students some fifteen minutes to extricate themselves. Most left the lecture hall rubbing the red marks where their skin was chafed and burned from the strings.

###

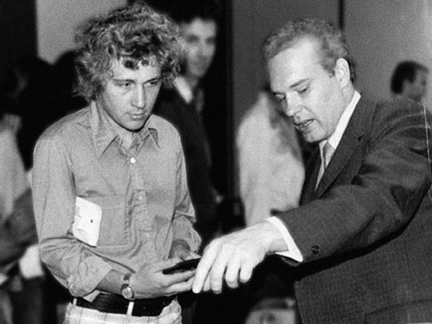

(The preceeding was an excerpt from Echo Detained, a novel that investigates Delasco’s theories to further the narrative arc. Peter Moss, Delasco’s former student and editor of his lectures, is in production of Ambrose Delasco’s biography, tentatively titled “A Mind Detained” and is due to be released in 2017 by Simon and Schuster. The photo at the top of this post is the only known photograph showing Moss and Delasco together, taken by an anonymous student circa 1966.)